what occurred in the workplace to bring about civil rights act of 1964 title vii

Folio Content

When William "Sonny" Walker was a college kid in Arkansas in the 1950s, he had to travel to Indiana to find summer jobs waiting tables because he was black and the segregated South didn't offering him much opportunity.

After he graduated and started teaching, he was paid about ii-thirds of what the white teachers earned beyond town in Fiddling Rock, Ark.

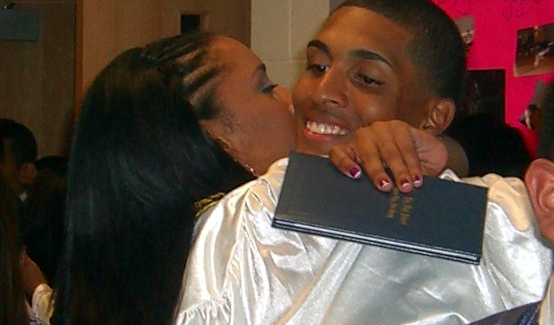

Now the retired ceremonious rights leader is 80, with grandchildren who had admission to meaningful internships and other opportunities during their summer breaks. Ane grandson is even the principal at a Little Rock school.

Walker, quondam head of the Martin Luther Rex Jr. Middle for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta, and others credit much of the change in the American workplace to the seminal Civil Rights Deed signed into police fifty years ago this summertime.

Title VII of the law outlawed employment discrimination based on race, sex, color, religion and national origin—and changed the thinking of Americans about the concept of fairness.

The Scope of Change

Today'southward higher students are baffled at the idea that it ever was acceptable to use factors such as race and gender to deny people jobs, says William P. Jones, a historian, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and expert on the civil rights move and the role of labor. But before Title 7, classified ads oft spelled out which genders and races could apply for item jobs.

As a male child in the early on 1970s, John Lewis Jr. tagged forth to his female parent's job equally a clerk at a Texas article of furniture store—a position she wouldn't take had a chance at getting before Title VII. He was young but immediately saw that she was the only black employee in the accounts payable department. He asked her, "Where am I going to work when I go an adult?"

Lewis, now 49, grew upward to become a lawyer and principal variety officeholder at Coca-Cola Co. in Atlanta. He oversees programs to identify diverse talent, to brand sure company policies don't unfairly affect certain segments of workers and to push Coke toward a goal of $i billion in spending annually on suppliers with minority owners.

"We've seen a dramatic shift in what is a only arroyo to employment," says Jones, writer ofThe March on Washington: Jobs, Liberty, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights(W.West. Norton & Co., 2013).

The larger Civil Rights Human action that included Title Seven came among sit down-ins, the March on Washington for Jobs and Liberty in 1963, and calls for the end of invidious discrimination that led to vastly dissimilar opportunities and treatment for whites and blacks. The law set out to end segregation in instruction and in public places and to protect the voting rights of minorities.

Title VII's ban on employment bigotry set up a whole new concept that individual employers could not discriminate in the workplace.

"It's 1 of the most important changes we run across resulting from the Civil Rights Deed," Jones says. "Changing the law actually did change people's minds because now it'south largely accepted as unjust to discriminate in employment based on race or gender."

Diverse Views

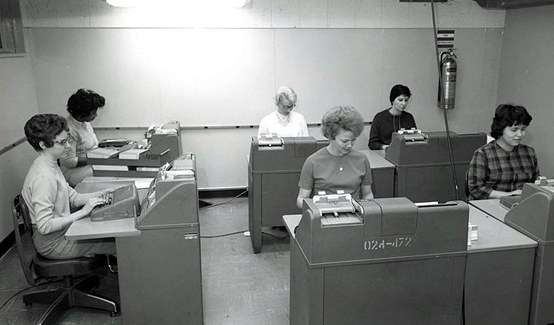

In terms of sheer numbers, women have arguably benefited the almost from the civil rights constabulary, says Jocelyn Frye, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, a think tank in Washington, D.C. Census figures bear witness that women made up nearly 47 pct of the civilian workforce in 2013—compared with about 29 percent in 1967, when Championship VII was still new.

Merely women most didn't get included. Equally Southern lawmakers fought bitterly against civil rights legislation, Rep. Howard W. Smith, a Virginia Democrat, added gender to the list of classes of people who couldn't exist discriminated confronting. Jones says there is some historical debate nigh whether Smith did it to try to draw more opposition to the Civil Rights Act and kill the measure, or whether he truly wanted women protected.

Merely women most didn't get included. Equally Southern lawmakers fought bitterly against civil rights legislation, Rep. Howard W. Smith, a Virginia Democrat, added gender to the list of classes of people who couldn't exist discriminated confronting. Jones says there is some historical debate nigh whether Smith did it to try to draw more opposition to the Civil Rights Act and kill the measure, or whether he truly wanted women protected.

Afterward, Congress expanded workplace protections beyond Championship Vii to include, for example, people with disabilities and older individuals.

The nation'south increasingly various demographics have meant that employers that discriminate would miss out on a larger pool of talent.

Minorities make upwards 35 per centum of the private industry workforce—about ten percentage points higher than in 1996, according to 2012 figures from the U.Southward. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Women and minorities however are underrepresented in many of the best-paying jobs, but less so than 50—or fifty-fifty 20—years agone.

Oneida D. Blagg, PHR, director of diverseness and employment practices at the University of Wyoming, says companies demand to make certain diversity besides extends to the executive offices, where less than 5 percent ofFortune 500 CEOs are women or minorities.

"Yous can't just talk most inclusion," says Blagg, a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who worked on equal employment opportunity in the military. "Your top ranks need to reflect the community you serve."

Many companies take realized that having a diverse staff helps them understand their customers better. Minorities represent 37 pct of the U.Due south. population at present, compared with less than 17 percent in 1970, U.S. Census Bureau figures show. "Diversity in the workforce today is a fiscal consequence," says Nicole Butts, SPHR, a Los Angeles-based client services director at Berkshire Associates, a Columbia, Dr.., human resource consulting company. "I demand to speak to my customer base, and my customer base is diverse."

Lewis agrees. Coca-Cola, he points out, is sold around the world to diverse consumers. Diverseness is "part of the differentiation of our make," he says. "It's also bringing diverse viewpoints to the table equally nosotros make of import decisions. The more diverse the room when decisions are made, the better the decisions."

Title VII with Teeth

Title Seven established the EEOC to enforce the police.

The resulting succession of numerous lawsuits accept helped define workplace protections, forced companies to modify unfair policies and practices, and given the law teeth. "Many of the man resources best practices that companies utilize are an outgrowth of equal employment cases," Butts says.

When Championship VII was showtime passed, many cases involved people who weren't hired because of their gender, race or other characteristics. However, over fourth dimension, the focus shifted from getting hired to fairness in promotions, says Douglas J. Farmer, a partner in San Francisco with police force firm Ogletree Deakins. Today, many cases involve terminations, he says.

Jonathan A. Segal, a partner at law firm Duane Morris in Philadelphia, says the proportion of his cases involving pay and promotion has increased from 15 percent fifteen years agone to nearly 35 per centum now.

The nature of discrimination has inverse, too. Unconscious bias has largely replaced overt discrimination. Segal says professionals demand to be wary of "like me" bias—managers favoring workers who remind them of themselves—and of recruiting for jobs through give-and-take-of-oral fissure, which attracts generally people demographically similar them.

The law does more than than just prohibit disparate treatment in hiring, promotion, and other deportment affecting the terms and conditions of employment, Farmer says. Information technology also bans discrimination that isn't intentional simply that has a discriminatory bear upon. For instance, firefighter promotion exams that had a disparate impact on the chances of women or minorities without a justifiable business concern need went up in smoke later on being challenged in the courts.

The EEOC handled nearly 94,000 charges under Title VII and other laws in 2013. The agency recovered $256 meg in monetary awards last year, non including what was recovered past those who went to court.

| Testify of Discrimination Douglas J. Farmer, an employment lawyer with Ogletree Deakins, finds it remarkable that there are still then many lawsuits 50 years after Title Seven became law. Part of the problem is that defining discrimination is not equally clear-cut as, say, showing that an employer has paid someone less than minimum wage. In Title VII cases, Farmer says, courts look at three kinds of show: |

|

|

|

More to Do

50 years may have been enough time to change the face up of the American workplace, but the journey toward workplace equality is far from over.

Figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that women earn 82 cents for every dollar a man makes. The figure at the start of 1979, past comparison, was 75 cents. (Still, earnings information do not adjust for types of occupations and years of experience.)

Some of the bug now are more subtle than, say, simply paying women a lower wage. For case, more needs to be done to make sure there is equal opportunity to get the plum jobs, Butts says. "We need to look at the decision-making that impacts pay—non just the pay itself," she explains.

And merely as the authors of Title VII didn't conceptualize the demand to include sexual orientation and disability condition in the law, other groups may emerge in the futurity to claim new protections.

Segal predicts that historic period bigotry may get an issue as Infant Boomers linger in jobs and Millennials itch to take their place. Workers with criminal records also accept gained attention due to minorities' disproportionate incarceration rates. (Encounter "Choices and Chances" as well in this issue.)

Procedurally, Farmer would like to encounter culling dispute resolution required to force both sides in a dispute to negotiate. For employers, going to trial is expensive and confusing as employees are called to testify. In addition, the outcomes are uncertain. Farmer compares a jury trial to betting all your money on one color on a roulette wheel. "There is no predictability in the system," he says.

He would also like to see better guidance and clearer tests from the courts that employers and workers can employ to understand when bigotry has taken identify.

Merely residuum is needed betwixt legislating diversity and taking a more organic arroyo, Lewis says. "While the laws are an important component, [and then too are] policy and culture and how we engage each other in a community."

HR departments have an important role to play, Segal says, by "looking at equal employment opportunity not just as a compliance consequence but as a value—make sure yous hire, mentor and promote the best and the brightest."

Frye says companies need to make sure managers and supervisors understand the police. "Employers who are on top of these issues are doing yearly grooming with managers and employees."

Employers are pushing for variety and fairness in the workforce for more than just altruistic reasons. "The purpose is then we tin thrive as companies and equally a state considering nosotros are taking advantage of this multifariousness of thought," Butts says, adding that "It only is good business organization."

Tamara Lytle is a freelance author in the Washington, D.C., area.

Source: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/pages/title-vii-changed-the-face-of-the-american-workplace.aspx

0 Response to "what occurred in the workplace to bring about civil rights act of 1964 title vii"

Postar um comentário